|

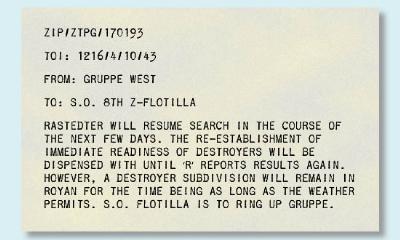

On 30 Sept. fishing vessels equipped with radar were detected in BF 8356 and 9271. If positive results are obtained by our air reconnaissance operating on the afternoon of 1 Oct. it is planned to send out our destroyer sub-division on 2 Oct. to seize the suspicious vessels … War Diary, Kriegsmarine Staff, Operations Division, 1 October 1943 The connection of detachment Rastedter with ASV operations may now be taken as established. CX/MSS/SALU WEST 829 (26 September–2 October 1943) Having taken off at around 2150 on the 1st, next morning He 111 “F” gave an estimated time of arrival at Bordeaux/Mérignac of 0530, approaching from the NW. Only four minutes out, he was notified that fog would prevent him from landing but it is not known where he was diverted. Meanwhile at 0422, another He 111 had taken off, apparently to co-operate with the two 8th Flotilla destroyers looking for Spanish trawlers suspected of carrying radar. It was back down by 0530 and the warships were told that fog had prevented "Rastedter's new take-off" so the operation was postponed to the following day. “F” duly set off again from Mérignac at 0418 on 3 October, its landing being reported at 1000. Another reconnaissance was flown on the 4th, from 0003–0916 but brought “negative result” and so the 8th Flotilla was stood down to normal notice.

In the early hours of 6 October the destroyers were told that another He 111 was airborne in search of the suspect trawlers and was expected to land between 0900 and 1000. What was new however was that a Ju 188, “G”, was to follow up at 1530; it was homing for a landing at Mérignac at 2016. An He 111 had also been due to take off around midday for a “direction-finding flight” over Arcachon Bay but whether this was an operational or a training sortie if not clear. However, the British analysts now felt they had enough information to add a note to their daily report: Fw 200, Ju 188 and He 111 aircraft have now all been identified in connection with operations of the Special Detachment at Bordeaux. The object of these operations may well be W/T interception. In other words these searches were now thought to be passive rather than active, listening for enemy transmissions. Another He 111 trawler-hunt was planned for 1300 the following day; passing in and out over the coast at Cap Ferret, the Heinkel was supposed to be in the air for seven or eight hours. Both an He 111 and the Ju 188 were to continue the search on the 8th, from 0106–1000 and 0620–1300 respectively, but no traffic was heard that would confirm that these flights had taken place. The next day, a signal at 0809 advised the 8th Destroyer Flotilla that the He 111 up since the early hours had yet to find anything. The Ju 188 was due to be aloft once more that afternoon. A crew from II./ZG 1 shot down on 8 October told their British interrogators that “crews had no instructions to note any Allied R/T messages which they might by chance intercept [they] were, however, aware that special R/T interception aircraft did operate over the Bay”. Messages referring to Rastedter by name led Bletchley Park’s Naval Section to deductions about current operations: An Oberleutnant Rastaedter [sic] was associated with A.S.V. He 111’s in the Mediterranean — a/c referred to … is therefore apparently an A.S.V. He 111 … and since [the] signal is addressed to [8th Destroyer] Flotilla, above a/c is presumably cooperating in the search. An He 111 due to fly on 10 October saw its mission cancelled by bad weather but another was able to take off at 0112 next morning. There was another operation intended early on the 14th but the weather again forced a cancellation on the 15th. Aircraft “F” was homing on Bordeaux from 0106 on the 18th; operations were cancelled and so another Heinkel due to have taken off at midnight may well not have done so. Unusually, an He 111 crossed out over the coast at midday on 20 October, heading for a position west of Brest; the following day saw two He 111 take off around midnight and a Ju 188 at 1000. 22 October: Spanish fishing vessels southwest of the Gironde and north of San Sebastian were searched without result by a group of minesweepers, as they were reported by the Luftwaffe to be suspected of carrying radar. 23 October: Eight Spanish fishing vessels, suspected of carrying radar on board, were searched without result by two patrol vessels ten miles north of San Sebastian. War Diary, Kriegsmarine Staff, Operations Division A single Heinkel was to fly in the small hours of the 24th and two again on the 28th. The following day represented a small landmark from the Allied point of view if not the Luftwaffe’s — to quote the Naval Section’s report for the 29th: ROUTINE NIGHT PATROL BY SPECIAL UNIT AT BORDEAUX 1 He 111 up 2359/28 in Bordeaux to cross coast West of Bordeaux, returning between 0800 and 0900/29. Aircraft was not heard in W/T. N.B. Previous description of these patrols as ASV patrols should be disregarded as evidence is inconclusive. In hindsight this re-evaluation and the one above seem overdue. While we cannot now be certain of all the factors contributing to the original interpretation it appears as if those concerned could see no operational value in repeatedly passing eight or nine hours over the sea at night if one was not actively searching with radar. It seems strange now that they did not think of anyone searching for radar (or other signals) when both sides had been doing just that since before the war. Two He 111 were operating on the 30/31st, taking off 15 minutes before and 15 minutes after midnight while on the last night of the month one Heinkel was due to take off at midnight, aircraft “X” being called without response by a Bordeaux ground station from 0344–0526.

On the 20th the Signals Branch had issued “Introduction to the workings and employment of shipping search sets in aircraft.” This included the Luftwaffe’s thinking about the effects of active radio countermeasures at sea: Jamming transmitters on land can render shipping targets, buoys and prominent points on the coast no longer recognisable. By situating such transmitters at favourable points along the coast … ships’ search radars … could be disrupted at quite long distances from land (up to 150 km if necessary). Where jamming activity is more limited, by turning down the sensitivity of the search set’s receiver and switching off its transmitter, it can be possible to home on the jammer and to establish definite landmarks. Jamming transmitters aboard ship work similarly to those on land. A formation of ships will only turn on its jammers if they think enemy aircraft have spotted them. In that case, accurate homing on individual ships of the formation can be impeded at night or in bad visibility. Ships proceeding alone may, when they are using a jammer, be homed on by aiming for the transmitter but without the possibility of measuring range. With jammers aboard aircraft, the enemy can complicate or hinder accurate homing on shipping targets or deceive our own aircraft and deflect them from their targets … Since the range of our own shipping search sets is doubled or tripled against jamming transmitters, it is to be expected that the enemy will operate jammers aboard ships and aircraft very sparingly and only in an emergency. continued on next page …

|

||||

The next day’s operations ended in some confusion thanks to misunderstandings between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. At 0100, Fw 200 F8+MK was to take off on a nine or 10-hour flight attempting to locate the supposed radar-carrying trawlers, only to report at 0210 that it was on its way back and would be landing in about 20 minutes. Already in the air, He 111 “F” was ordered to take over from the Focke-Wulf and report the position of any suspect vessels. A further signal to “F” from Fliegerführer Atlantik at 0600 was misinterpreted by Kap. z. See Ermendenger who soon reported his ships at immediate readiness, intending to sail at 0702. It took three-quarters of an hour before it was explained that the Flifü’s signal was to an aircraft, not to the destroyers, and that they could stand down as no trawlers had been found. By this time, Heinkel “F” had already returned to base.

The next day’s operations ended in some confusion thanks to misunderstandings between the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine. At 0100, Fw 200 F8+MK was to take off on a nine or 10-hour flight attempting to locate the supposed radar-carrying trawlers, only to report at 0210 that it was on its way back and would be landing in about 20 minutes. Already in the air, He 111 “F” was ordered to take over from the Focke-Wulf and report the position of any suspect vessels. A further signal to “F” from Fliegerführer Atlantik at 0600 was misinterpreted by Kap. z. See Ermendenger who soon reported his ships at immediate readiness, intending to sail at 0702. It took three-quarters of an hour before it was explained that the Flifü’s signal was to an aircraft, not to the destroyers, and that they could stand down as no trawlers had been found. By this time, Heinkel “F” had already returned to base.